“Sculpture is an exorcism,” Louise Bourgeois once told an interviewer. “When you are really depressed and have no other way out except suicide, sculpture will get you out of it.” It’s the voice of a lifelong extremist: Give me art or give me death.

It may not be surprising that the works for which Bourgeois (1911-2010) is best known today are a series of gargantuan spiders which have been exhibited all around the world, from the Turbine Hall of Tate Modern in London (1999), to more than twenty locations in the subsequent decade, from New York to Tokyo to St. Petersburg. Many people have an irrational fear of spiders but Bourgeois found something comforting in these predators.

“I came from a family of repairers,” Bourgeois said. “The spider is a repairer. If you bash into the web of a spider, she doesn’t get mad. She weaves and repairs it.”

The family, which ran a thriving business restoring and selling old tapestries, was not a happy one. In 1982, the year she was given a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Bourgeois created an autobiographical text-and-photo project for Artforum, called Child Abuse. For the first time she revealed how her father had brought his mistress into the household as a governess for his three children. This woman, Sadie, would stay for ten years, while Louise’s mother accepted the arrangement without complaint.

For Louise, the favourite daughter, the situation would leave severe psychic scars. She recognised her father’s cruelty, but eventually came to feel that her mother had played an even more duplicitous game. “I am a pawn,” Bourgeois wrote in Child Abuse. “Sadie is supposed to be there as my teacher and actually you, mother, are using me to keep track of your husband. This is child abuse.”

Bourgeois felt triply betrayed, by both of her parents, and by her teacher, Sadie. In later life she recognised how urgently she had wanted to win her father’s favour in competition with her mother. But the addition of a fourth person threw the classic Oedipal triangle into disarray. “Competition with the mother is one thing,” Bourgeois wrote, “but competition with a chosen favourite is unthinkable, intolerable”.

For much of Bourgeois’s life she harboured feelings of resentment for her father, and for Sadie, but under the influence of psychoanalysis she found it was the cool, strategic attitude of her mother that had left the deepest scars. The monstrous spider that thrilled crowds at Tate Modern was called Maman.

“My best friend was my mother and she was deliberate, clever, patient, soothing, reasonable, dainty, subtle, indispensable, neat, and as useful as a spider,” Bourgeois recalled. Yet all these qualities only instilled a sense of fear in the child, who felt controlled and manipulated by a woman who refused to rebel against her husband’s outrageous behaviour. Josephine Bourgeois became ‘the bad mother’ whose sangfroid chilled her offspring. For psychoanalysts such as Karl Abraham, when a spider appeared in a patient’s dreams it was a symbol of the Bad Mother.

As if in reaction to Josephine’s coolness, Louise Bourgeois’s entire life was filled with anxiety. She suffered from fits of catatonic depression and violent rages. She was jealous, cruel and mischievous, at times openly sadistic. Each outburst would be subject to bouts of remorse.

When Bourgeois married the American art historian Robert Goldwater in 1938, and moved to New York, she felt her life had been saved. Through Robert she soon became acquainted with America’s most important artists, professors, curators and dealers. Her own career got off to a promising start, with totem-like wooden sculptures such as Sleeping Figure (1950), which was acquired by MoMA; and the iconic Femme Maison (1946-47)—a drawing of woman’s body in which the torso and head has been replaced by a house from which two tiny arms emerge.

Everything came to a halt in 1953 when Bourgeois withdrew completely, refusing to exhibit for ten years. During that decade she kept working while wrestling with her inner demons. These were the years that saw the avant-garde shuffling its way through Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism and Hard-Edge. For guru critics such as Clement Greenberg, progress in art meant a rejection of illusion and theatricality, but Bourgeois’s sensibility was profoundly theatrical.

Her re-emergence owed a debt to the rise of Feminism and its championing of neglected female artists, but it was also a symptom of the waning of hardline modernist ideology. Bourgeois made sculptures in plaster, stone, wood, metal and marble. She drew obsessively in abstract and surrealist styles. The work was deeply personal, filled with riotous sexual symbolism. The most notorious piece was Fillette (1968), a lumpen, bronze phallus she would tuck under her arm for a 1982 portrait photo by Robert Mapplethorpe.

An article in the New Yorker quotes Bourgeois saying “that when Mapplethorpe asked to photograph her she was afraid; she knew that his work was about men with big penises. So she brought her penis, Fillette, carrying it jauntily under her arm like an Hermès handbag.” Because fillette means ‘little girl’, the title may seem slightly bizarre, but it fits neatly into Bourgeois’s family mythology. Having already given birth to two daughters, Josephine Bourgeois would have liked to present her husband, Louis, with a son. Instead, she settled for naming the third daughter in his honour. Little Louise would rapidly become her father’s favourite, although this would prove to be a burden rather than a privilege. Louise was a girl who took on the role of a boy, symbolised by the bronze phallus.

For an artist who spoke continuously of her fears, it might seem that Bourgeois was surprisingly willing to confront such sources of anxiety. For most of her stop-start career as an artist she refused to discuss “private matters” but in later life she willingly related everything back to the stories revealed to the world in her Child Abuse article. In this she bears comparison to another female artist with whom she was acquainted in New York during the 1960s. Yayoi Kusama (b.1929) had the same compulsion to talk about her fears while confronting them in the most public fashion. Kusama spoke openly about her “fear of sex”, but became known for orchestrating nude happenings and orgies. In the sculptural works she called Accumulations she covered objects and even rooms with phallic shapes made from fabric.

The seeming contradiction between both women’s lifelong neuroses and their extroverted behaviour raised questions as to how much we may trust their self-analyses. In 1986 Bourgeois explained: “I am very experienced in the process of seducing … That’s what I’m interested in: how do I seduce that person. And I am not talking about self-expression. Self-expression is the pits!” The seducer will say whatever is necessary to attain his or her goal, whereas self-expression allows too many demons, too many flaws and weaknesses to surface. Seduction is a game, but self-expression implies a degree of honesty that may reveal too much. Both Bourgeois and Kusama chose the path of seduction—which entailed a rampant theatricality—rather than succumb to the idea of victimhood.

Bourgeois’s true awakening would come in the 1980s, following the death of her husband in 1973 and the success of her MoMA retrospective. The final two decades of her life would be extraordinarily productive, as her newfound popularity brought in enough income to allow her to realise any project she desired. It saw an explosion of dark fantasy—not just the spiders, but a seated, headless dog with multiple breasts The She-Fox (1983); a bronze, male torso curled back on itself, suspended in air Arch of Hysteria (1993), and a series of stark, large-scale installations called Cells in which the remains of human activity lie scattered in cheerless iron cages, like crime scenes.

Bourgeois’s central theme was the body in pieces. Massed penile shapes; breasts clustered like grapes on a vine; disembodied eyes, ears and hands; shapeless dolls and mannequins grappling carnivorously with each other. By dredging her subconscious for such images, the artist was facing her deepest fears and fantasies. As she grew more and more unwilling to leave her apartment her imagination worked at a feverish pace. She used assistants for welding, carving and sewing, but would draw through the night in marathon, insomniac sessions. Her work was a compulsion, if not a pathology. Her images are so bound up with her own psyche that they defy categorisation.

“I live in chaos,” she said, “with an unrewarded passion for order”. That chaos was almost a pre-condition for Bourgeois’s extravagant creativity, as she drew on those anxieties unleashed in childhood which could be harnessed but never extinguished. Like the spider she didn’t get mad, she simply kept on repairing.

For more visit www.theeastonfoundation.org

Image Credits:

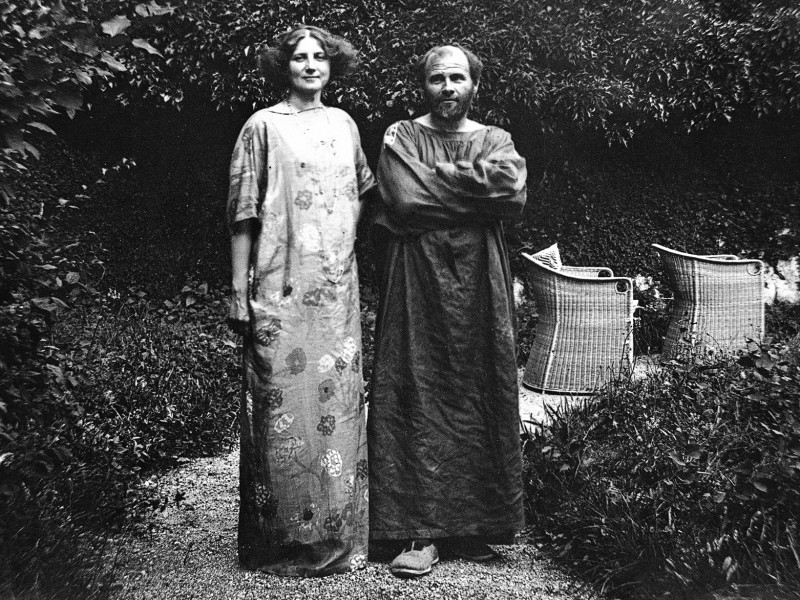

Image 01. Photo by Christian Ohde/McPhoto/ullstein bild via Getty Images.

Image 02. Louise Bourgeois In and Out, 1995. Metal, glass, plaster, fabric and plastic Cell: 205.7 x 210.8 x 210.8 cm. Plastic: 195 x 170 x 290 cm. Photo: Christopher Burke © The Easton Foundation/VAGA, NY/VISCOPY, Sydney.

Image 03. Photo by Stephane De Sakutin/AFP/Getty Images.

Image 04. Louise Bourgeois The She-Fox, 1985. Black marble and steel 56 1/2 × 20 1/2 × 30 1/4 in. (143.5 × 52 × 76.8 cm) Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Gift of Camille Oliver- Hoffmann, 2008.22 Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago

Related Features

-

127

-

-

-