The sculptural works of Belgian artist Wim Delvoye are strewn with winding helixes, spiralling ladders, windmills, wheels and coiled digestive tracts, whose movements lead us around, back to the beginnings. These elusive, twisting motifs evoke an ambivalence with regards to notions of progress—rather than advancing forwards, we encounter things in states of contorted escape and evasion, turning away and unweaving themselves.

For his major exhibitions at the Louvre in Paris (2012), and the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow (2014), Delvoye installed a series of twisted statues amongst the more ‘straight’ objects of the permanent collections. In these works, familiar art historical motifs like busts, putti and the Pietà are reproduced with high definition stereolithography 3D printing technology, before having their forms twisted—either clockwise or anticlockwise—to the near limits of legibility.

Produced in polished bronze or white lacquered resin that appears like solid marble, and often displayed on neoclassical plinths, these alluring twisted statues resemble the originals in their scale, materiality and presentation, but the features of the images are warped through the spiralling, so that what we encounter is more like fleeting, unbound energies than fixed forms. In Delvoye’s swirled variation on a Daphnis and Chloé statue by Mathurin Moreau, for instance, the figures of the innocent lovers are caught up in a vigorous writhing motion that renders their separate bodies almost indistinguishable.

In the artist’s Holy Family series of bronze statues, the crucifixion—perhaps the most iconic image in all of Western art history—is looped back on itself, so the cross carrying the body of Christ is turned into a ring or a möbius strip. There are varying versions of these works; sometimes the punished body is stretched out along the outside of the ring, sometimes it is contracted into the inside. Sometimes there are two möbius crucifixions interlocked, sometimes there are several nestled inside of one another. The overall effect is one of history simultaneously coiling into itself and twisting away from itself, an exaggeration that threatens to obliterate the object’s original meaning entirely.

Besides the religious and art historical references, Delvoye also draws from the more mundane of inspiration as his source material. Twisted Dump Truck (2011), for example, takes the form of a garbage truck and renders it in astoundingly intricate laser cut steel latticework, resembling the architecture of gothic cathedrals, before twisting the form around so that one end of the truck curls down on its side. The usually clunky and purely functional object becomes something surprisingly seductive here, appearing as if it is in the midst of a private dance or contortion.

This work is part of an ongoing series where heavy industrial machinery—including cement mixers and bulldozers—meet with graceful gothic motifs, buttresses and spires. The production of these works is an elaborate process; each structure in the gothic series takes around one year to produce, and involves the outsourced labour of computer experts, mathematicians, laser cutters and metal welders at various locations around the world.

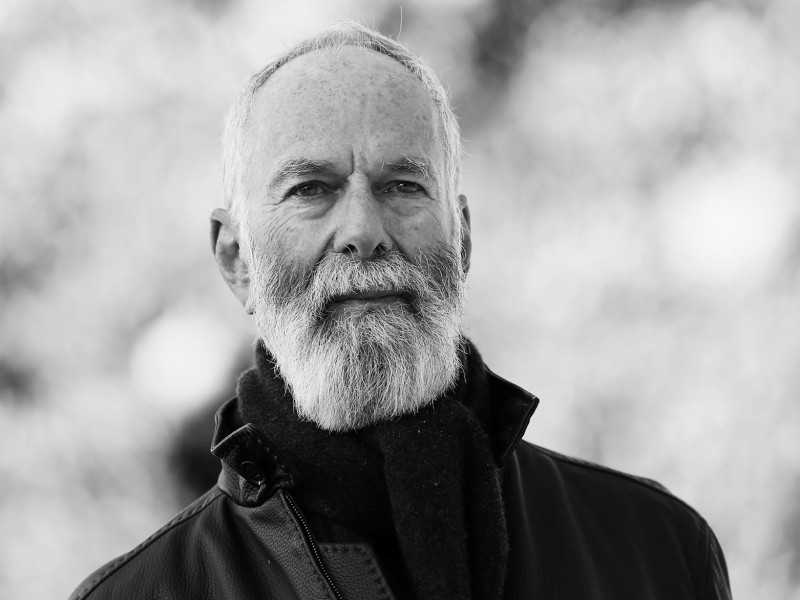

Speaking with me over the phone from his studio in Gent, Delvoye remarks that the recurrence of spiral and helix images in his work is “probably something for the psychoanalysts to figure out”. What he likes, though, is that twisting forms can address the three-dimensionality of the space, inviting viewers to move around, to circumnavigate the object and its surroundings. These sculptures cannot be fully perceived from any single point of view—they are three-dimensional situations, that must be encircled and flirted with from an array of perspectives before they can appear.

While he enjoys creating these immersive environments, Delvoye tells me he also endorses two-dimensional documentation and the online circulation of photos of his art. “There is not one official front to photograph, so these sculptures invite people to take their own pictures,” he says, “and depending on where they stand, they have a different picture”. Amateur visitor photographs can even become another criteria for judging the success of an artwork, Delvoye remarks: “If rich people buy it for however much—that’s one criteria used often in the press, but there’s a lot of other criteria like Google or Instagram, very interesting criteria which don’t have a lot to do with money. Then it’s more to do with the crowd than with capital.”

Delvoye’s work took a decidedly biological turn in the late nineties with his Cloaca project—which he still considers to be his most important work. The Cloaca—Latin for ‘sewer’ or ‘toilet’—is a large scale, artificial model of digestion that performs the physical and chemical labour of transforming food into faeces. When installed in an exhibition space, the Cloaca machines are fed with fresh sustenance daily. Simulated mechanical mastication then prepares the food for its encounter with stomach-like acids, followed by the introduction of intestinal bacteria and finally dehydration in preparation for excretion. Imitating the digestive stages of the human stomach and intestines, the process produces unique, occasionally oppressive odours into the gallery space in which it is sited. Festering, sludge like residues are slowly built up on the once pristine organs of the apparatus, eventually producing a small deposit of something that closely resembles real human faeces.

In reimagining this obscure and abject process as an externalised cultural spectacle, Delvoye has exaggerated the dynamics of desire and valorisation that underpin the art market. Here, even literal ‘shit’ can become a precious art object—mirroring the alchemical transformation of undifferentiated geological base matter into refined gold. Some collectors have managed to acquire their own Cloaca produced specimen, preserved within its own branded vacuum sealed plastic bag, for a princely sum of US $1,000.

“Even the old Romans had proverbs and jokes where money was always related to shit,” says Delvoye, “and somehow it’s the first money you give to your mother. Your mother takes care of you and you pay something back to her with excrement. The first economic transaction, for your food, you are paying with shit to your mother. Your mother seems to be very happy and even strokes your butt—as soon as you shit you get this reward, butt stroking. So it is something that, from early childhood onward, is a connection that most people, in most cultures have to one another. And money is also very dirty, I mean physical money, it is very dirty, people are touching it, it goes from one person to another, it’s full of bacteria and it can make you sick.”

Like the human organism it imitates, Delvoye’s Cloaca has also evolved, undergoing numerous permutations and refinements over time. The earliest versions appeared as a horizontal series of cylindrical glass tanks linked by tubes, with each tank performing a single function. Later versions of the Cloaca began to mirror the verticality of the human form, which elevates the producer above their abject product. In one version there are three washing machines, stacked on top of each other with a mouth and an anus crowning each end in turn. This move, toward the use of opaque mechanised objects in place of the transparent glass tanks, might also be read as a desire to conceal the acquired shame of the organism’s natural function.

By blurring the lines between the exhibition plinth and the toilet, Delvoye has updated the ready made technique exemplified by Duchamp’s 1917 Fountain urinal, investing it with the anxieties and quandaries of contemporary scientific preoccupations. At a public unveiling of a Cloaca at Casino Luxembourg in 2007, an audience member asked if any of the methane gas was being harvested for its capacity as a biofuel. “No, it all goes to waste,” responded Delvoye with glee. In a utopian sense, the Cloaca cannot be understood as an attempt to finesse or refine models of consumption, but merely as consumption of these models in its own right.

Related Features

-

127

-

-

-