This May, the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art will unveil its new exhibition devoted to Rei Kawakubo. Kawakubo will become the first living designer honoured with a monographic show since Yves Saint Laurent in 1983. The exhibition follows Miuccia Prada, who was co-honoured alongside Elsa Schiaparelli four years ago, celebrating a lineage of sororal figureheads who have changed the way women dress. “To have to be sexy? That I hate,” Prada once said. “To be outrageously sexy? That I love.” It’s difficult to imagine Kawakubo’s complicit wink; she rarely seems okay with wrapping the body for seduction.

In 1981, when Kawakubo presented at Paris Fashion Week for the first time, her collection of ragged and fey clothes sent tremors through the fashion press—who called the look “Hiroshima’s Revenge”. Over the years she has balanced the violence with wistfulness. Her signatures include mossy appliqués, crumbling flowers made of ashen tulle, tumorous billows and bumps, pouch like crinolines, and funeral veils worn over grisly makeup. Her knitted sweaters have been punched with holes, then wryly called ‘Comme des Garçons lace’. The Japanese philosophy of wabi-sabi—that nothing in the universe is complete, permanent, or perfect—is one that Kawakubo constantly strains toward in her work. “I like it when something is off, not perfect,” the designer told Harold Koda, former chief curator of the Costume Institute. “We loosen a screw of the machine here and there so they can’t do exactly what they’re supposed to do.”

Kawakubo was born in Tokyo in 1942, the eldest of her parents’ three children and their only daughter. In 1960, Kawakubo enrolled in Keio University, where her father was an administrator and took a degree in Aesthetics—a major that included the study of Asian and Western art. By the end of the sixties, Kawakubo was working as a freelance stylist to finance the production of her own girlish sportswear line, which she would often use in her own projects. Comme des Garçons was incorporated in 1973 and met considerable success with a forward clientele who enjoyed the graceful notes in her irreverent clothes. But Kawakubo was becoming increasingly challenged by the urge to innovate. “I felt I should be doing something more directional, more powerful,” she told the New York Times. “In fashion we had to get away from the influence of what had been done in the 1920s or the 1930s. We had to get away from the folkloric. I decided to start from zero.”

The elastic area of “in-betweenness” is where Kawakubo exerts her supremacy, according to a statement by the Costume Institute. Her frustrations with “beauty, good taste, and fashionability” are worked out in collections that seesaw on the porous line between “East/West, male/female and past/present”. You often hear people say that Kawakubo “invented” black, by which they mean she upturned its Western tradition as the colour of mourning, to become the colour of defiance—the men and women Kawakubo dresses being called ‘black crows’. Koda wrote that Kawakubo’s clothes are “Intuitive and reactive solutions [that] violate the very fundamentals of apparel”.

Kawakubo is notoriously media shy and has often commented that whatever is readily known about her work is simply journalists’ projections of what they think they see. If she has anything to say about fashion, it seems to be this: conventional beauty is a blessing doomed to expire. Her clothes are an affront to sanctioned style, even when she appears to be catering to popular narratives of femininity, such as bridehood. The designer, who once told Elle that “one’s lifestyle should not be affected by the formality of marriage,” left her audience awed with 2005s Broken Brides collection. She delivered a procession of serene girls with their faces covered in mime makeup, wearing haunting crimped lace gowns, with leg of mutton sleeves and tulle that fell like cobwebs. The spectacle was comedic in a poignant way, and in opportune flashes, the virgin brides appeared eager to consolidate their powers at the altar.

For Spring 2012, Kawakubo played with this notion through the presentation of White Drama. It was a collection of pure materials draped with impure fun. Kawakubo fashioned duchesse satin into a large bow that bound the arms; on another model, the flowering lace of a christening gown looked like a funeral offering. But when Kawakubo wants to amplify the idea, she doesn’t make clothes at all. Her weird abstractions, according to Koda, are ultimately studies in “disengagement from the debasing whiff of utility”. Only in specific contexts, like the runway, do her clothes reveal to you just how dense they are with sinister reference. The queer shapes and robotic folds perform best when you wear the clothes as Kawakubo seems to encourage you to: as a knowing and willing accomplice to their bewitching allure.

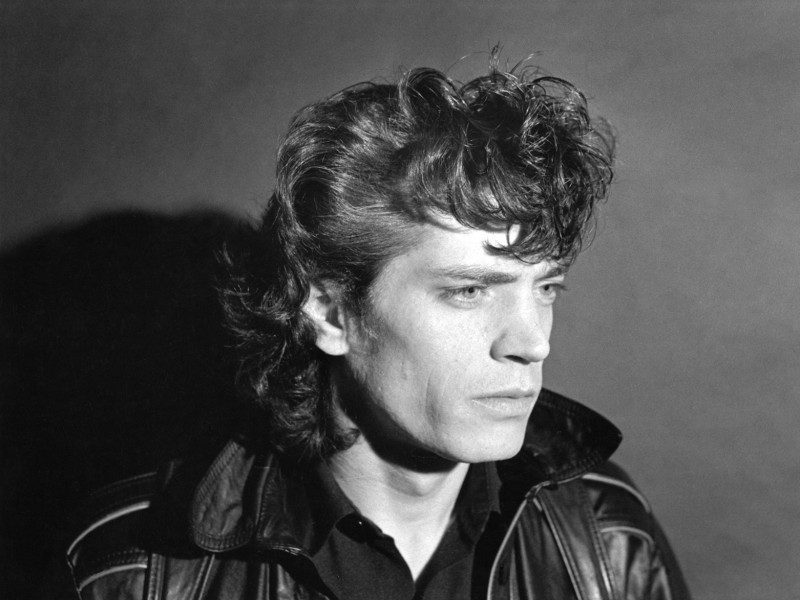

Devotees who lack the means or courage to wear Kawakubo’s creations will often choose a piece from Comme des Garçons casual wear line Play, which is recognisable for its open-eyed heart logo. Play is winsome where the mainline is fearsome, less a gateway line and more a synthesised wardrobe of punkish design. Kawakubo feels an “affinity to the punk spirit,” because it is “against flattery” she told 032c. Fans wear the signature Play stripes with ease. You’re likely to see it under a neon romper, or a leather jacket, or peeking out from under the collar of a starchy suit.

Not surprisingly, Kawakubo recoils from the idea of hero worship and told The New Yorker, “For me belief means you have to depend on somebody”. She is rightly considered to be the designers’ designer, due to her relentless commitment to creating a body of work that is singular in its authority. Young fashion students are still absorbing—and in many cases, discovering—her genius in the cutting room, where moody layers and bulbous silhouettes manifest themselves. Kawakubo’s oeuvre is difficult to imitate for one simple reason: she will always be a moving target.

Related Features

-

137

-

-

-